Party time

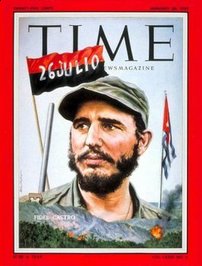

The most sacred of all days in the communist Cuba's political calendar is the 26th of July. It marks the day in 1953 when Fidel Castro and a group of mostly young, middle-class, Catholic twentysomethings stormed the Moncada Barracks in the city of Santiago de Cuba, the second largest in the country.

The idea behind the attack was to spark off a national rebellion against Fulgencio Batista, who had staged a coup d'etat a year earlier. Instead, the attack was a military disaster: the Army, which remained loyal to Batista, easily withstood the ill-prepared assault, a few of the rebels were killed, many were captured and sent to prison, including Castro, and for a time at least, Batista seemed untouchable.

But in the longer term, the Moncada attack was a public relations master stroke for Castro. All of sudden, the young lawyer from Oriente province became something of a curiosity in the Cuban media and indeed, in the media outside Cuba. He was sent to prison, then was released as part of a national amnesty, left for Mexico and then, in 1956, arrived back in Cuba along with a few other exiles to toppled Batista. It was the beginning of a military and propaganda campaign that would result in Castro entering Havana triumphally in January 1959.

As a child growing up in Cuba during the 1960s and early 1970s, I remember el 26 de Julio well and not just because it was a public holiday. On the 26th of July, Castro would give what was supposed to be the most important speech of the year. As I recount in Child of the Revolution, a million habaneros would congregate in the Plaza de la Revolucion back then - many by choice, others because they had no choice – to hear El Comandante en Jefe speak for five or six hours. And there was no escape. The ceremony would be broadcast live on all television stations and on all radio stations and next day or the day after, the entire speech would be published in the newspapers, word for word, ovation after obligatory ovation … Pages and pages and pages of words that even the most revolutionary Cubans, like some of my uncles, would never, ever read.

The more things change …

This year, the 26th of July was celebrated not in Havana but in the city of Bayamo, in the eastern end of the island, not far from where Castro was born and not all that far, either, from the town of Banes, where I grew up.

The numbers were down considerably, as you would expect in a smaller region – about 100,000 according to the Cuban official media - but Castro still managed to speak for two and a half hours, which sounds impressive for a man about to turn 80. He spent the time doing what he has always done: plucking meaningless figures from the air to show how well things are going in Cuba; comparing Cuban health statistics with those in selected capitalist countries (they are always better in Cuba, of course); encouraging his new friends in Latin America, such as Hugo Chavez and Evo Morales, to "fight imperialism"; warning yet again of that impending invasion by the United States that never seems to eventuate; and on and on … All of it faithfully recorded by a sycophantic, government-controlled media.

But Castro did make a promise. Or it sounded like a promise. Claiming that more Cubans are now reaching the ripe old age of 100 thanks to his Government's outstanding social services, Castro added: "But our little neighbours to the North should not fear - I am not planning to be in office at that age.”

So, there you have it. The good news and the bad news all rolled into one: 20 more years. As Cubans would say, se cago la cosa!