Those Castro Rumours

I guess we will find out soon enough whether Fidel Castro is really dead or not. Even in a place like Cuba, where all media are controlled by the regime and where no one ever knows for sure what the upper echelons of the Communist hierarchy are up to, you can’t keep such big news hidden forever. Or can you? The Soviets were reasonably successful back in the early 1980s in keeping the West in the dark about just how sick Leonid Brezhnev really was, so you never know … Mind you, in the end, it didn’t do the old Bolsheviks any good.

Given the latest round of Castro speculation, I thought I’d share with you a brief “opinion” I wrote for a program called Perspective, which airs on Radio National, one of several networks that form part of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). As the name of the program suggests, this is one of those programs were guests are given about five minutes to give a personal perspective on a topic of their choosing.

Mine went to air in late June, as part of the publicity push in Australia and New Zealand for the launch of Child of the Revolution: Growing Up in Castro’s Cuba. This is an edited version. You can read the full version as it went to air, by going here.

Perspective: Cuba

Cuba today is a country paralised by death. A death foretold.

Visitors to Havana return talking about a city – indeed, a whole country – anxiously waiting for the inevitable: the day Fidel Castro dies.

Castro has been in power now for 47 years. Most Cubans today have lived under no other regime. They have known no other leader. He turns 80 in August. He is frail and some say, verging on the senile, but very much still in control. And increasingly thinking about his legacy.

In a recent speech to students at Havana University, Castro raised the issue no one else in Cuba ever raises publicly: what will happen when he dies.

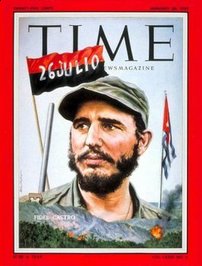

This wasn’t the youthful Castro you see in those romantic, black and white photographs from the 1960s, but a pessimistic old man admitting for the first time that well, yes, he is mortal. It was a rare moment of honesty in what passes for Cuban political life.

This wasn’t the youthful Castro you see in those romantic, black and white photographs from the 1960s, but a pessimistic old man admitting for the first time that well, yes, he is mortal. It was a rare moment of honesty in what passes for Cuban political life.

Castro is right to be worried about his legacy. He is right to be fearful about his own place in history … because there is absolutely no guarantee that things will stay the same in Cuba once he is gone.

His designated successor is his own brother, Raul, the second most powerful man in Cuba in his capacity as First Vice President and more importantly, Minister for the Armed Forces - a post the younger Castro has held coincidentally, for 47 years. But even Castro is questioning the viability of his own succession plan. He recently pointed out to a visiting French journalist what is patently obvious to everyone else: Raul is only five years younger – and his health is not all that great.

Instead, Castro said, Cubans could look to a younger generation of potential revolutionary leaders, aged in their 40s and 50s, like the Second Vice-President, Carlos Lage, or the dogmatic Minister for Foreign Affairs, Felipe Perez Roque.

The reality, of course, is that most Cubans are unlikely to warm up to the idea of leaving their future in the hands of dull bureaucrats like Lage or ideologically-driven apparatchiks like Perez Roque.

I suspect what most Cubans want – but cannot say to tourists lest they find themselves behind bars – is change. Cubans today, especially young Cubans, want to be able to start thinking for themselves, rather than having to continue to parrot the same old, tired slogans written for them by octogenarians.

For me, this sense of desperately wanting things to change was best illustrated by a recent Cuban-Spanish film, Habana Blues, that played at the Sydney Spanish Film Festival. While keeping within the bounds of censorship that have ruled Cuban cultural life since 1959 – that is, you never, ever criticise Castro - Habana Blues highlighted in surprisingly stark terms the palpable impatience of millions of young Cubans.

These are children of the Revolution looking for change. They want to be able to travel overseas. They want to be able to express themselves in music, in film and in writing without that pervasive fear of repercussion.

I suspect most young Cubans today want to be able to decide their own destiny, rather than have it decided for them by an 80 year old man who is said by Forbes magazine to have accumulated a fortune worth more than $US900 million.

I think that is why Castro is fearful. Because he knows that once he goes, the whole edifice will almost certainly come crashing down.

Given the latest round of Castro speculation, I thought I’d share with you a brief “opinion” I wrote for a program called Perspective, which airs on Radio National, one of several networks that form part of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). As the name of the program suggests, this is one of those programs were guests are given about five minutes to give a personal perspective on a topic of their choosing.

Mine went to air in late June, as part of the publicity push in Australia and New Zealand for the launch of Child of the Revolution: Growing Up in Castro’s Cuba. This is an edited version. You can read the full version as it went to air, by going here.

Perspective: Cuba

Cuba today is a country paralised by death. A death foretold.

Visitors to Havana return talking about a city – indeed, a whole country – anxiously waiting for the inevitable: the day Fidel Castro dies.

Castro has been in power now for 47 years. Most Cubans today have lived under no other regime. They have known no other leader. He turns 80 in August. He is frail and some say, verging on the senile, but very much still in control. And increasingly thinking about his legacy.

In a recent speech to students at Havana University, Castro raised the issue no one else in Cuba ever raises publicly: what will happen when he dies.

This wasn’t the youthful Castro you see in those romantic, black and white photographs from the 1960s, but a pessimistic old man admitting for the first time that well, yes, he is mortal. It was a rare moment of honesty in what passes for Cuban political life.

This wasn’t the youthful Castro you see in those romantic, black and white photographs from the 1960s, but a pessimistic old man admitting for the first time that well, yes, he is mortal. It was a rare moment of honesty in what passes for Cuban political life.Castro is right to be worried about his legacy. He is right to be fearful about his own place in history … because there is absolutely no guarantee that things will stay the same in Cuba once he is gone.

His designated successor is his own brother, Raul, the second most powerful man in Cuba in his capacity as First Vice President and more importantly, Minister for the Armed Forces - a post the younger Castro has held coincidentally, for 47 years. But even Castro is questioning the viability of his own succession plan. He recently pointed out to a visiting French journalist what is patently obvious to everyone else: Raul is only five years younger – and his health is not all that great.

Instead, Castro said, Cubans could look to a younger generation of potential revolutionary leaders, aged in their 40s and 50s, like the Second Vice-President, Carlos Lage, or the dogmatic Minister for Foreign Affairs, Felipe Perez Roque.

The reality, of course, is that most Cubans are unlikely to warm up to the idea of leaving their future in the hands of dull bureaucrats like Lage or ideologically-driven apparatchiks like Perez Roque.

I suspect what most Cubans want – but cannot say to tourists lest they find themselves behind bars – is change. Cubans today, especially young Cubans, want to be able to start thinking for themselves, rather than having to continue to parrot the same old, tired slogans written for them by octogenarians.

For me, this sense of desperately wanting things to change was best illustrated by a recent Cuban-Spanish film, Habana Blues, that played at the Sydney Spanish Film Festival. While keeping within the bounds of censorship that have ruled Cuban cultural life since 1959 – that is, you never, ever criticise Castro - Habana Blues highlighted in surprisingly stark terms the palpable impatience of millions of young Cubans.

These are children of the Revolution looking for change. They want to be able to travel overseas. They want to be able to express themselves in music, in film and in writing without that pervasive fear of repercussion.

I suspect most young Cubans today want to be able to decide their own destiny, rather than have it decided for them by an 80 year old man who is said by Forbes magazine to have accumulated a fortune worth more than $US900 million.

I think that is why Castro is fearful. Because he knows that once he goes, the whole edifice will almost certainly come crashing down.

1 Comments:

You know, those Castro rumours have been around for a long time. They must come either from some lunatic in Cuba or some wishful thinking in Miami.

Post a Comment

<< Home